Listen

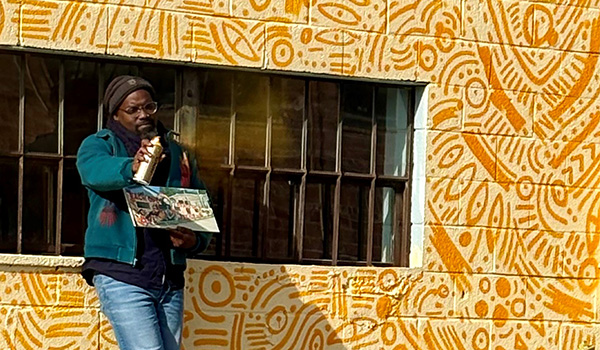

Carl Johnson and tenants [24]

In the 1960s, Asheville’s public housing communities were racially segregated, with Black residents living in Hillcrest Apartments and Lee-Walker Heights, and low-income White residents living in Pisgah View Apartments.

In December 1967, Black tenants of Hillcrest Community took a stand against squalid living conditions in the Black-only complexes in the form of a rent strike, using the slogan “We are human and we want our freedom” as their rallying cry. Strikers demanded that their rights as tenants and citizens be honored by the Asheville Housing Authority (AHA) even as many residents were threatened with eviction if they made complaints.

Carl Johnson, president of the Hillcrest Tenants’ Association and a retired employee of the VA hospital, led the movement. Along with improving living conditions, Mr. Johnson and fellow strikers demanded that the AHA’s executive director Carl Vaughn step down from his position.

In less than 48 hours, the AHA recruited 11 temporary maintenance workers to attend to tenants' needs. Mr. Johnson was not impressed, and told The Asheville Citizen on December 9, 1967, "These men have been hired for three to six weeks, [and] we don’t regard this as any step toward getting what we are asking for."

The strike continued into the new year. In late January 1968, tenants from Lee-Walker Heights joined the movement, and Vaughn announced his resignation.

W. Jennings Groome assumed the role of executive director of the AHA on Feb. 27, and the strike concluded shortly after the AHA formalized in writing the list of improvements it planned to make.

Mr. Johnson commended Mr. Groome’s work later that year in the Asheville Citizen-Times. “As far as I am concerned, the executive director is doing everything in his power to satisfy complaints that were raised during the rent strike,” he told the paper.

Earning the moniker "the Mayor of Hillcrest," Mr. Johnson wielded his experiences as a political force to empower young activists in effecting change. Asheville civic leader Isaac Coleman described Mr. Johnson to the Asheville Citizen-Times by saying, "People knocked on his door late at night with some kind of problem, and he'd climb out of bed, go to the door, and listen to them," Coleman said. "Come see me tomorrow, and we'll work out the problem.”